Posts Tagged ‘gov2.0’

How to help build the UK’s open planning database: writing scrapers

This post is by Andrew Speakman, who’s coordinating OpenlyLocal’s planning application work.

As Chris wrote in his last post announcing OpenlyLocal’s progress in building an open database of planning applications, while we can do the importing from the main planning systems, if we’re really going to cover the whole country, we’re going to need the community’s help. I’m going to be coordinating this effort and so I thought it would be useful to explain how we’re going to do this (you can contact me at planning@openlylocal.com).

First, we’re going to use the excellent ScraperWiki as the main platform for writing external scrapers. It supports Python, Ruby and PHP, and has worked well for similar schemes. It also means the scraper is openly available and we can see it in action. We will then use the Scraperwiki API to upload the data regularly into OpenlyLocal.

Second, we’re going to break the job into manageable chunks by focus on target groups of councils, and just to sweeten things – as if building a national open database of planning applications wasn’t enough 😉 – we’re going to offer small bounties (£75) for successful scrapers for these councils.

We have some particular requirements designed to make the system maintainable, and do things the right way, but not many are fixed in stone, so feel free to respond with suggestions if you want to do it in a different way.

For example, the scraper should keep itself current (running on a daily basis), but also behave nicely (not putting an excessive load on Scraperwiki or the target website by trying to get too much data in one go). In addition we propose that the scrapers should operate by updating current applications on a daily basis and also make inroads into the backlog by gathering a batch of previous applications.

We have set up three example scrapers that operate in the way we expect: Brent (Ruby), Nuneaton and Bedworth (Python) and East Sussex (Python). These scrapers perform 4 operations, as follows:

- Create new database records for any new applications that have appeared on the site since the last run and store the identifiers (uid and url).

- Create new database records of a batch of missing older applications and store the identifiers (uid and url). Currently the scrapers are set up to work backwards from the earliest stored application towards a target date in the past

- Update the most current applications by collecting and saving the full application details. At the moment the scrapers update the details of all applications from the past 60 days.

- Update the full application details of a batch of older applications where the uid and url has been collected (as above) but the application details are missing. At the moment the scrapers work backwards from the earliest “empty” application towards a target date in the past

The data fields to be gathered for each planning application are defined in this shared Google spreadsheet. Not all the fields will be available on every site, but we want all those that are there.

Note the following:

- The minimal valid set of fields for an application is: ‘uid’, ‘description’, ‘address’, ‘start_date’ and ‘date_scraped’

- The ‘uid’ is the database primary key field

- All dates (except date_scraped) should be stored in ISO8601 format

- The ‘start_date’ field is set to the earliest of the ‘date_received’ or ‘date_validated’ fields, depending on which is available

- The ‘date_scraped’ field is a date/time (RFC3339) set to the current time when the full application details are updated. It should be indexed.

So how do you get started? Here’s a list of 10 non-standard authorities that you can choose from. Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire, Ashfield, Bath, Calderdale, Carmarthenshire, Consett, Crawley, Elmbridge, Flintshire. Have a look at the sites and then let me know if you want to reserve one and how long you think it will take to write your scraper.

Happy scraping.

Planning Alerts: first fruits

Well, that took a little longer than planned…

[I won’t go into the details, but suffice to say our internal deadline got squeezed between the combination of a fast-growing website, the usual issues of large datasets, and that tricky business of finding and managing coders who can program in Ruby, get data, and be really good at scraping tricky websites.]

But I’m pleased to say we’ve now well on our way to not just resurrecting PlanningAlerts in a sustainable, scalable way but a whole lot more too.

Where we’re heading: a open database of UK planning applications

First, let’s talk about the end goal. From the beginning, while we wanted to get PlanningAlerts working again – the simplicity of being able to put in your postcode and email address and get alerts about nearby planning applications is both useful and compelling – we also knew that if the service was going to be sustainable, and serve the needs of the wider community we’d need to do a whole lot more.

Particularly with the significant changes in the planning laws and regulations that are being brought in over the next few years, it’s important that everybody – individuals, community groups, NGOs, other websites, even councils – have good and open access to not just the planning applications in their area, but in the surrounding areas too.

In short, we wanted to create the UK’s first open database of planning applications, free for reuse by all.

That meant not just finding when there was a planning application, and where (though that’s really useful), but also capturing all the other data too, and also keep that information updated as the planning application went through the various stages (the original PlanningAlerts just scraped the information once, when it was found on the website, and even then pretty much just got the address and the description).

Of course, were local authorities to publish the information as open data, for example through an API, this would be easy. As it is, with a couple of exceptions, it means an awful lot of scraping, and some pretty clever scraping too, not to mention upgrading the servers and making OpenlyLocal more scalable.

Where we’ve got to

Still, we’ve pretty much overcome these issues and now have hundreds of scrapers working, pulling the information into OpenlyLocal from well over a hundred councils, and now have well over half a million planning applications in there.

There are still some things to be sorted out – some of the council websites seem to shut down for a few hours overnight, meaning they appear to be broken when we visit them, others change URLs without redirecting to the new ones, and still others are just, well, flaky. But we’ve now got to a stage where we can start opening up the data we have, for people to play around with, find issues with, and start to use.

For a start, each planning application has its own permanent URL, and the information is also available as JSON or XML:

There’s also a page for each council, showing the latest planning applications, and the information here is available via the API too:

There’s also a GeoRSS feed for each council too allowing you to keep up to date with the latest planning applications for your council. It also means you can easily create maps or widgets for the council, showing the latest applications of the council.

Finally, Andrew Speakman, who’d coincidentally been doing some great stuff in this area, has joined the team as Planning editor, to help coordinate efforts and liaise with the community (more on this below).

What’s next

The next main task is to reinstate the original PlanningAlert functionality. That’s our focus now, and we’re about halfway there (and aiming to get the first alerts going out in the next 2-3 weeks).

We’ve also got several more councils and planning application systems to add, and this should bring the number of councils we’ve got on the system to between 150 and 200. This will be an ongoing process, over the next couple of months. There’ll also be some much-overdue design work on OpenlyLocal so that the increased amount of information on there is presented to the user in a more intuitive way – please feel free to contact us if you’re a UX person/designer and want to help out.

We also need to improve the database backend. We’ve been using MySQL exclusively since the start, but MySQL isn’t great at spatial (i.e. geographic) searches, restricting the sort of functionality we can offer. We expect to sort this in a month or so, probably moving to PostGIS, and after that we can start to add more features, finer grained searches, and start to look at making the whole thing sustainable by offering premium services.

We’ll be working too on liaising with councils who want to offer their applications via an API – as the ever pioneering Lichfield council already does – or a nightly data dump. This not only does the right thing in opening up data for all to use, but also means we don’t have to scrape their websites. Lichfield, for example, uses the Idox system, and the web interface for this (which is what you see when you look at a planning application on Lichfield’s website) spreads the application details over 8 different web pages, but the API makes this available on a single URL, reducing the work the server has to do.

Finally, we’re going to be announcing a bounty scheme for the scraper/developer community to write scrapers for those areas that don’t use one of the standard systems. Andrew will be coordinating this, and will be blogging about this sometime in the next week or so (and you can contact him at planning at openlylocal dot com). We’ll also be tweeting progress at @planningalert.

Thanks for your patience.

An open letter to Vince Cable

Dear Mr Cable

I read with interest yesterday your letter to the Prime Minister about some of the issues facing the UK in the future, and in particular the need for a vision and for a connected approach across government. This struck me as timely and useful, as it hopefully signalled the intention of a change in policy at one of the main roadblocks to innovation in improving government and fostering innovation.

I am referring to the policy of your own department – the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills – to restricting access to core reference datasets, such as the Ordnance Survey mapping data, postcodes, and company data, and thus not just stifling innovation and growth but preventing a consistent and connected approach across government.

Though much about the future is unclear one thing is certain, that we are increasingly living in a data world. In that world innovation – and democracy – depends on the ability to access and reuse data, particularly the core reference data on which other data is based: what area a postcode refers to, where something is located, who runs and owns the companies for which we work or which receive government money.

In fact, opening non-personal government data forms part of the government’s growth agenda, and it has already published a considerable amount. Yet much of this data is almost useless without the core reference to tie it together – data which is under the control of your department.

When I met with your then junior minister Ed Davey a couple of months ago on this subject, I asked him point blank whether the government was going to publish huge amounts of data under a licence which allowed free reuse, but was going to restrict access to the core datasets which tied these together, that were in fact the core infrastructure for our digital world? He said, ‘We’ve got some ideas for innovative charging models.’

Let’s put aside the fact that government departments aren’t the right people to come up with ‘innovative charging models’ – they don’t have the right skills, experience, and unlike entrepreneurs like myself they aren’t risking their personal money, but the nation’s future. Let’s focus instead on a ‘connected approach across government’. This would seem a perfect example of a relatively minor source of revenue (maybe as little as £50 million, according to the report published yesterday by Policy Exchange) preventing such an approach, and with it a route to how the UK will ‘earn our living in the future’.

In my own area, OpenCorporates has in a year grown to be the largest open database of corporate data in the world – without, I should add, any help, encouragement or cooperation from BIS. We have just released a new feature that allows search for directors across multiple jurisdictions, massively increasing the ability of journalists, fraud investigators, investors, civil society, customers and suppliers to understand companies. Needless to say, UK companies aren’t included in this list because this data is restricted to those who pay.

One vision for the future would include making the UK a genuinely open and transparent place to do business, for example making UK Companies House as open as that in New Zealand, where all data is available openly and without charge. It would include making the UK leaders in the field of open data, not just generating a world-leading ecosystem of companies such as we have in motorsport, but pioneering the use of open data by companies of all types and sizes. And it would include the government being able to reuse and publish its own data without the corrosive and restrictive licences placed upon it by the likes of Ordnance Survey, and thus have a truly connected approach.

You have it within your power to help enable that vision – I hope you will act on it.

Chris Taggart

Co-founder & CEO, OpenCorporates, founder OpenlyLocal.com

Member of Local Public Data Panel

The economics of open data & the big society

Yesterday I received an email from a Cabinet Office civil servant in preparation for a workshop tomorrow about the Open Data in Growth Review, and in it I was asked to provide:

an estimation of the impact of Open Data generally, or a specific data set, on UK economic growth… an estimation of the economic impact of open data on your business (perhaps in terms of increase in turnover or number of new jobs created) of Open Data or a specific data set, and where possible the UK economy as a whole

My response:

How many Treasury economists can I borrow to help me answer these questions? Seriously.

Because that’s the point. Like the faux Public Data Corporation consultation that refuses to allow the issue of governance to be addressed, this feels very much like a stitch-up. Who, apart from economists, or those large companies and organisations who employ economists, has the skill, tools, or ability to answer questions like that.

And if I say, as an SME, that we may be employing 10 people in a year’s time, what will that count against Equifax, for example (who are also attending), who may say that their legacy business model (and staff) depends on restricting access to company data. If this view is allowed to prevail, we can kiss goodbye to the ‘more open, more fair and more prosperous‘ society the government says it wants.

So the question itself is clearly loaded, perhaps unintentionally (or perhaps not). Still, the question was asked, so here goes:

I’m going to address this in a somewhat reverse way (a sort of proof-by-contradiction). That is, rather than work out the difference between an open data world and a closed data one by estimating the increase from the current closed data world, I’m going to work out the costs to the UK incurred by having closed data.

Note that extensive use is made of Fermi estimates and backs of envelopes

- Increased costs to the UK of delays and frustrations. Twice this week I have waited around for more than 10 minutes for buses, time when I could have stayed in the coffee shop I was working in and carried on working on my laptop had I known when the next bus was coming.

Assuming I’m fairly unremarkable here and the situation happens to say 10 per cent of the UK’s working population through one form of transport or another, that means that there’s a loss of potential productivity of approx 0.04% (2390 minutes/2400 mins x 10%).

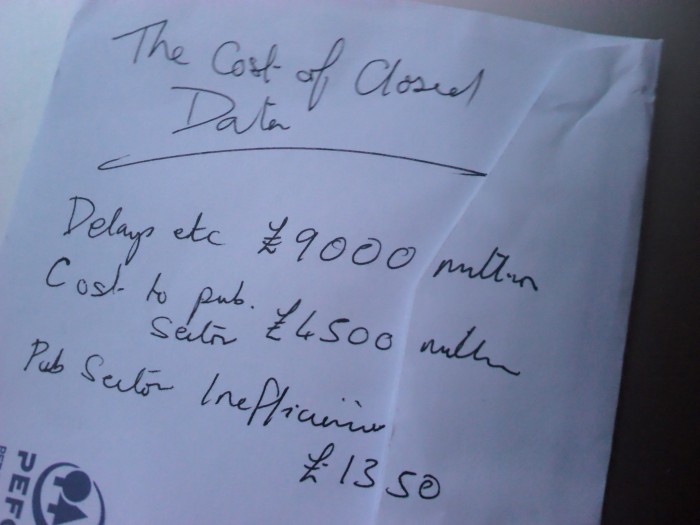

Similar factors apply to a whole number of other areas, closely tied to public sector data, from roadworks (not open data) to health information to education information (years after a test dump was published we still don’t have access to Edubase) – just examine a typical week and think of the number of times you were frustrated by something which linked to public information (strength of mobile signal?). So, assuming that the transport is a fairly significant 10% of the whole, and applying it to the UK $2.25 trillion GDP we get £9000 million. Not included: loss of activity due to stress, anger, knock-on effects (when I am late for a meeting I make attendees who are on time unproductive too), etc- Knock-on cost of data to public sector and associated administration. Taking the Ordnance Survey as an example of a Shareholder Executive body, of its £114m in revenue (and roughly equivalent costs), £74m comes from the public sector and utilities.

Although there would seem to be a zero cost in paying money from one organisation to another, this ignores the public sector staff and administration costs involved in buying, managing and keeping separate this info, which could easily be 30% of these costs, say 22 million. In addition, it has had to run a sales and marketing operation costing probably 14% of its turnover (based on staff numbers), and presumably it costs money collecting, formatting data which is only wanted by the private sector, say 10% of its costs.

This leads to extra costs of £22m + £16m + £14m = £52 million or 45%. Extrapolating that over the Shareholder Executive turnover of £20 billion, and discounting by 50% (on the basis that it may not be representative) leads to additional costs of £4500 million. Not included: additional costs of margin paid on public sector data bought back from the private (i.e. part of the costs when public sector buys public-sector-based data from the private sector is the margin/costs associated with buying the public sector data).- Significant decreases in exchange of information, and duplication of work within the public sector (not directly connected with purchase of public sector data). Let’s say that duplication, lack of communication, lack of data exchange increases the amount of work for the civil service by 0.5%. I have no idea of the total cost of the local & central govt civil service, but there’s apparently 450,000 of them, earning, costing say £60,000 each to employ, on the basis that a typical staff member costs twice their salary. That gives us an increased cost of £1350 million. Not included: cost of legal advice, solving licence chain problems, inability to perform its basic functions properly, etc.

- Increased fraud, corruption, poor regulation. This is a very difficult one to guess, as by definition much goes undetected. However, I’d say that many of the financial scandals of the past 10 years, from mis-selling to the FSA’s poor supervision of the finance industry had a fertile breeding ground in the closed data world in which we live (and just check out the FSA’s terms & conditions if you don’t believe me). Not to mention phoenix companies, one hand of government closing down companies that another is paying money to, and so on. You could probably justify any figure here, from £500 million to £50 billion. Why don’t we say a round billion. Not included: damage to society, trust, the civic realm

- Increased friction in the private sector world. Every time we need a list of addresses from a postcode, information about other companies, or any other public sector data that is routinely sold, we not only pay for it in the original cost, but for the markups on that original cost from all the actors in the chain. More than that, if the dataset is of a significant capital cost, it reduces the possible players in the market, and increases costs. This may or may not appear to increase GDP, but it does so in the same way that pollution does, and ultimately makes doing business in the UK more problematic and expensive. Difficult to put a cost on this, so I won’t.

- I’m also going to throw in a few billion to account for all the companies, applications and work that never get started because people are put off by the lack of information, high barriers to entry, or plain inaccessibility of the data (I’m here taking the lead from the planning reforms, which are partly justified on the basis that many planning applications are not made because of the hassle in doing them or because they would be refused, or otherwise blocked by the current system.)

What I haven’t included is reduced utilisation of resources (e.g empty buses, public sector buildings – the location of which can’t be released due to Ordnance Survey restrictions, etc), the poor incentives to invest in data skills in the public sector and in schools, the difficulty of SMEs understanding and breaking into new markets, and the inability of the Big Society to argue against entrenched interests on anything like and equal footing.

And this last point is crucial if localism is going to mean more rather than less power for the people.

So where does that leave us. A total of something like:

£17,850 million.

That, back of the envelope-wise, is what closed data is costing us, the loss through creating artificial scarcity by restricting public sector data to only those pay. Like narrowing an infinitely wide crossing to a small gate just so you can charge – hey, that’s an idea, why not put a toll booth on every bridge in London, that would raise some money – you can do it, but would that really be a good idea?

And for those who say the figures are bunk, that I’ve picked them out of the air, not understood the economics, or simply made mistakes in the maths – well, you’re probably right. If you want me to do better give me those Treasury economists, and the resources to use them, or accept that you’re only getting the voice of those that do, and not innovative SMEs, still less the Big Society.

Footnote: On a similar topic, but taking a slightly different tack is the ever excellent David Eaves on the economics of Toronto’s transport data. Well worth reading.

Update 15/10/2011: Removed line from 3rd para: ” (it’s also a concern that we’re actually the only company attending that’s consuming and publishing open data)” . In the event it turned out there were a couple other SMEs too working with open data day-to-day, but we were massively outnumbered by parts of government and companies whose existing models were to a large degree based on closed data. Despite this there wasn’t a single good word to be heard in favour of the Public Data Corporation, and many, many concerns that it was going down the wrong route entirely.

The Public Data Corporation vs Good Governance

As I feared back when it was first announced, the proposed UK Public Data Corporation has got nothing to do with open data, and everything to do with protecting the interests of a few civil servants, turning back the open data clock to the dark ages of derived data and privileged access for the few.

However, the issue I’d like to focus on here, having last week attended a workshop on the PDC consultation is governance. [It’s worth mentioning that I was the only one at the workshop without a stake in the existing public sector information structure, telling in itself.] And far from it being a dry, academic, wonkish subject, it is critical to the future of public data in the UK.

The reason this is so contentious is twofold:

- The consultation on the PDC has been drawn very narrowly, trying to get respondants to choose between a set of options that are all bad for open data, and ultimately democracy. “So, open data, would you like a bullet to the back of the head, or to be slowly drained of blood?”

- There are clear conflicts of interest between the wider interests of society, and those of the Shareholder Executive – the trading funds such as the Ordnance Survey and Land Registry who are the very roadblock that open data is supposed to clear, but yet who crucially seem to be driving the PDC.

Now, from their perspective, I can see the appeal of keeping everything cosy and tight, particularly if there’s a chance the organisations being floated off, and with it considerable personal enrichment. But public policy shouldn’t be driven by the personal interests of civil servants, but what is in the interests of society as a whole.

In fact, the governance of the Public Data Corporation, and the rules by which it operates were the one thing that everyone at the workshop I attended agreed upon. In fact more than that, it was agreed that the delivery of its duties should be separate both from the principles by which it operates (which should be for the benefit of society) and the independent body that needs to ensure it sticks to those principles.

But here’s the kicker, the Transition Board for the PDC (which will oversee its membership, structure and governance) is, I understand, meeting on October 25, two days before the consultation ends.

When I asked this meeting, and whether the consultation was a done deal, I was told, “The governance of the PDC is not being consulted on.”

This is both rather shocking, and shameful, and for me means there’s only one viable option if the UK is serious about open data: to send the whole PDC concept back to the drawing board, and this time to come up with a solution that is focused not on civil servants’ narrow personal interests, but on building a ‘more open, more fair and more prosperous‘ society (to quote the Chancellor).

Open Data: A threat or saviour for democracy?

This is my presentation to the superb OKCON2011 conference in Berlin last week. It’s obviously openly licensed (CC-BY), so feel free to distribute widely. Comments also welcome.

When Washington DC took a step back from open data & transparency

When the amazing Emer Coleman first approached me a year and a half to get feedback on the plans for the London datastore, I told her that the gold standard for such datastores was that run by the District of Columbia, in the US. It wasn’t just the breadth of the data; it was that DC seemed to have integrated the principles of open data right into its very DNA.

And we had this commitment in mind that when we were thinking which were the US jurisdictions we’d scrape first for OpenCorporates, whose simple (but huge) goal is to build an open global database of every registered company in the world.

While there were no doubt many things that the DC company registry could be criticised for (perhaps it was difficult for the IT department to manage, or problematic for the company registry staff), for the visitors who wanted to get the information it worked pretty well.

What do I mean by worked well? Despite or perhaps because it was quite basic, it meant you could use any browser (or screenreader, for those with accessibility issues) to search for a company and to get the information about it.

It also had a simple, plain structure, with permanent URLs for each company, meaning search engines could easily find the data, so that if you search for a company name on Google there’s a pretty good chance you’ll get a link to the right page. This also means other websites can ‘deep-link’ to the specific company, and that links could be shared by people, in social networking, emails, whatever.

Finally, it meant that it was easy to get the information out of the register, by browsing or by scraping (we even used the scraper we wrote on ScraperWiki as an example of how to scrape a straightforward company register as part of our innovative bounty program).

It was, for the most part, what a public register should be, with the exception of providing a daily dump of the data under an open licence.

So it was a surprise a couple of weeks ago to find that they had redone the website, and taken a massive step back, essentially closing the site down to half the users of the web, and to those search engines and scrapers that wanted to get the information in order to make it more widely available.

In short it went from being pretty much open, to downright closed. How did they do this? First they introduced a registration system. Now, admittedly, it’s a pretty simple registration process, and doesn’t require you to submit any personal details. I registered as ‘Bob’ with a password of ‘password’ just fine. But as well as adding friction to the user experience, it also puts everything behind the signup out of the reach of search engines. Really dumb. Here’s the Google search you get now (a few weeks ago there were hundreds of thousands of results):

The other key point about adding a registration system is that the sole reason is to be able to restrict access to certain users. Let me repeat that, because it goes to the heart of the issue about openness and transparency, and why this is a step back from both by the District of Columbia: it allows them to say who can and can’t see the information.

If open data and transparency is about anything, it’s about giving equal access to information no matter who you are.

The second thing they did was build a site that doesn’t work for those who don’t use Internet Explorer 7 and above, including those who used screenreaders. That’s right. In the year 2011, when even Microsoft are embracing web standards, they decided to ditch them, and with them nearly half the web’s users, and all those who used screenreaders (Is this even allowed? Not covered by Americans With Disabilities Act?).

In the past couple of weeks, I’ve been in an email dialogue with the people in the District of Columbia behind the site, to try to get to the bottom of this, and the bottom seems to be, that the accessibility of the site, the ability for search engines to index it, and for people to reuse the data isn’t a priority.

In particular it isn’t a priority compared with satisfying the needs of their ‘customers’, meaning those companies that file their information (and perhaps more subtly those companies whose business models depend on the data being closed). Apparently some of the companies had complained that they were being listed, contacted and or solicited without their approval.

That’s right, the companies on the public register were complaining that their details were public. Presumably they’d really rather nobody had this information. We’re talking about companies here, remember, who are supposed to thrive or fail in the brutal world of the free market, not vulnerable individuals.

It’s worth mentioning here that this tendency to think that the stakeholders (hate that word) are those you deal with day-to-day is a pervasive problem in government in all countries, and is one of the reasons why they are failing to benefit from open data the way they should and failing too to retool and restructure for the modern world.

Sure, we can work around these restrictions and probably figure out a way to scrape the data, but it’s a sad day to see one of the pioneers of openness and transparency take such a regressive step. What’s next? Will the DC datastore take down its list of business licence holders, or maybe the DC purchase order data, all of which could be used for making unsoliticited requests to these oversensitive and easily upset businesses?

p.s. Apparently this change was in response to an audit report, which I’ve asked for a copy of but which hasn’t yet been sent to me. Any sleuthing or FOI requests gratefully received.

p.p.s. I also understand there’s also new DC legislation that’s been recently been passed that require further changes to the website, although again the details weren’t given to me, and I haven’t had time to search the DC website for them

George Osborne’s open data moment: it’s the Treasury, hell yeah

As a bit of an outsider, reading the government’s pronouncements on open data feels rather like reading official Kremlin statements during the Cold War. Sometimes it’s not what they’re saying, it’s who’s saying it that’s important.

And so it is, I think, with George Osborne’s speech yesterday morning at Google Zeitgeist, at which he stated, “Our ambition is to become the world leader in open data, and accelerate the accountability revolution that the internet age has unleashed“, and “The benefits are immense. Not just in terms of spotting waste and driving down costs, although that consequence of spending transparency is already being felt across the public sector. No, if anything, the social and economic benefits of open data are even greater.”

This is strong, and good stuff, and that it comes from Osborne, who’s not previously taken a high profile position on open data and open government, leaving that variously to the Cabinet Office Minister, Francis Maude, Nick Clegg & even David Cameron himself.

It’s also intriguing that it comes in the apparent burying of the Public Data Corporation, which got just a holding statement in the budget, and no mention at all in Osborne’s speech.

But more than that it shows the Treasury taking a serious interest for the first time, and that’s both to be welcomed, and feared. Welcomed, because with open data you’re talking about sacrificing the narrow interests of small short-term fiefdoms (e.g. some of the Trading Funds in the Shareholder Executive) for the wider interest; you’re also talking about building the essential foundations for the 21st century. And both of these require muscle and money.

It also overseas a number of datasets which have hitherto been very much closed data, particularly the financial data overseen by the Financial Services Authority, the Bank of England and even perhaps some HMRC data, and I’ve started the ball rolling by scraping the FSA’s Register of Mutuals, which we’ve just imported into OpenCorporates, and tying these to the associated entries in the UK Register of Companies.

Feared, because the Treasury is not known for taking prisoners, still less working with the community. And the fear is that rather than leverage the potential that open data allows for a multitude of small distributed projects (many of which will necessarily and desirably fail), rather than use the wealth of expertise the UK has built up in open data, they will go for big, highly centralised projects.

I have no doubt, the good intentions are there, but let’s hope they don’t do a Team America here (and this isn’t meant as a back-handed reference to Beth Noveck, who I have a huge amount of respect for, and who’s been recruited by Osborne), and destroy the very thing they’re trying to save.

What’s that coming over the hill, is it… the Public Data Corporation?

A couple of days ago, there was a brief announcement from the UK Government of plans for a new Public Data Corporation, which would “bring together Government bodies and data into one organisation”.

A good thing, no? Well, up to a point, Lord Copper.

I tweeted after the announcement: “Is it just me, or does the tone of the Public Data Corp make any other #opendata types uneasy?” From the responses, I clearly wasn’t the only one, and in my discussions since then it’s clear there’s a lot of nervousness out there.

So, what is it, and should we be afraid? The answers are ‘Nobody knows’, and ‘Yes’.

To flesh that out a bit, none of the open data activists and developers that I’ve spoken to knows what it is, or what the real motivation is, and remember these are the people who did much to get us into a place where the UK government has declared that the public has a ‘Right To Data’ and that the excellent ‘Open Government Licence‘ should be the default licence.

In that context, the announcement of a ‘Public Data Corporation’ should be be treated with some wariness.

However, this wariness turns into suspicion, when you read the press release.

First the announcement is a joint one from the Cabinet Office minister Francis Maude (who seems to very much get the need for open public data in the changed world in which we live) and from Business Minister Edward Davey, who I know nothing about, but his department BIS (Dept of Business, Innovation & Skills) has very much not been pushing for open data, and in fact has in the past refused to make data it oversees openly available.

(My sources tell me the proposal in fact originated from BIS, and thus could be seen as an attempt by the incumbents to co-opt the open data agenda, as a way of shutting it down, smothering it if you like.)

Second, despite the upbeat headline “Public Data Corporation to free up public data and drive innovation” (Shock horror: org states its aim is to innovate & be successful), the text contains a number of worrying statements:

- “By bringing valuable Government data together, governed by a consistent set of principles around data collection, maintenance, production and charging[my emphasis], the Government can share best practice, drive efficiencies and create innovative public services for citizens and businesses. The Public Data Corporation will also provide real value for the taxpayer.”

The idea of ‘value for the taxpayer’ is the same old stuff that got us into the unholy mess of trading funds, and the gordian knot of the Ordnance Survey licence wich is still being unpicked. This nearly always translates as value we can measure in £s, which in turn means what income we’ve got coming in (even if it’s from other public sector bodies). - “It will provide stability and certainty for businesses and entrepreneurs, attracting the investment these operations need to maintain their capabilities and drive growth in the economy” – quote from Edward Davey.

If I were a cynic I’d say stability and certainty translates to stagnation and rent-seeking businesses, which may be music to civil servants’ ears but does nothing to help innovation. We’re in a rapidly changing world. Get over it. - “bringing valuable Government data together, governed by a consistent set of principles around data collection, maintenance, production and charging”.

If this is the PDC’s mandate I think it could end up focused on the last of these, short-sighted though that would be. - “It will also provide opportunities for private investment in the corporation.”

Great. A conflicting priority, to delight the bureaucrats and muddy the focus. Keep it small, keep it simple, keep it agile.

Finally, there’s no mention of open data, no mention of the Open Government Licence, the Transparency Board and only one mention of transparency, and that’s in Francis Maude’s quote.

As Tom Steinberg (a member of the Transparency Board) wrote in a thread about the PDC on MySociety developer mailing list ”

If you’re a natural cynic, you’ll just say the government has already decided to flog everything off to the highest bidder. If you adopt that position, and give up without a fight, the people in Whitehall and the trading funds who want to do that will almost certainly win.

However, if you believe me when I say things are finely balanced, that either side could win, and enough well-organised external pressure could really make a difference over the next year, then you won’t just bitch, you’ll get stuck in.

He’s not wrong there. We’ve got perhaps 6 months to make this story turn out good for open data, and good for the wider community, and I suspect that means some messy battles along the way, forcing government to take the right path rather than slide into its bad old habits, perhaps with some key datasets, which should undoubtedly be public open data, but are currently under a restrictive licence.

I’ve got a couple in my sights. Watch this space.

Videoing council meetings revisited: the limits of openness in a transparent council

A couple of months ago, I blogged about the ridiculous situation of a local councillor being hauled up in front of the council’s standards committee for posting a council webcast onto YouTube, and worse, being found against (note: this has since been overturned by the First Tier Tribunal for Local Government Standards, but not without considerable cost for the people of Brighton).

At the time I said we should make the following demand:

Give the public the right to record any council meeting using any device using Flip cams, tape recorders, frankly any darned thing they like as long as it doesn’t disrupt the meeting.

Step forward councillor Liam Maxwell from the Royal Borough of Windsor & Maidenhead, who as the cabinet member for transparency has a personal mission to make RBWM the most transparent council in the country. I don’t see why you couldn’t do that our council, he said.

So, last night, I headed over to Maidenhead for the scheduled council meeting to test this out, and either provide a shining example for other councils, or show that even the most ‘transparent’ council can’t shed the pomposity and self-importance that characterises many council meetings, and allow proper open access.

The video below, less than two minutes long, is the result, and as you can see, they chose the latter course:

Interestingly, when asked why videoing was not allowed, they claimed ‘Data Protection’, the catch-all excuse for any public body that doesn’t want to publish, or open up, something. Of course, this is nonsense in the context of a public meeting, and where all those being filmed were public figures who were carrying out a civic responsibility.

There’s also an interesting bit to the end when a councillor answered that they were ‘transparent’ in response to the observation that they were supposed to be open. This is the same old you-can-look-but-don’t touch attitude that has characterised much of government’s interactions with the public (and works so well at excluding people from the process). Perhaps naively, I was a little shocked to hear this from this particular council.

So there you have it. That, I guess, is where the boundaries of transparency lies at Windsor & Maidenhead. Why not test them out at your council, and perhaps we can start a new scoreboard at OpenlyLocal to go with the open data scoreboard, and the 10:10 council scoreboard