Posts Tagged ‘data’

The economics of open data & the big society

Yesterday I received an email from a Cabinet Office civil servant in preparation for a workshop tomorrow about the Open Data in Growth Review, and in it I was asked to provide:

an estimation of the impact of Open Data generally, or a specific data set, on UK economic growth… an estimation of the economic impact of open data on your business (perhaps in terms of increase in turnover or number of new jobs created) of Open Data or a specific data set, and where possible the UK economy as a whole

My response:

How many Treasury economists can I borrow to help me answer these questions? Seriously.

Because that’s the point. Like the faux Public Data Corporation consultation that refuses to allow the issue of governance to be addressed, this feels very much like a stitch-up. Who, apart from economists, or those large companies and organisations who employ economists, has the skill, tools, or ability to answer questions like that.

And if I say, as an SME, that we may be employing 10 people in a year’s time, what will that count against Equifax, for example (who are also attending), who may say that their legacy business model (and staff) depends on restricting access to company data. If this view is allowed to prevail, we can kiss goodbye to the ‘more open, more fair and more prosperous‘ society the government says it wants.

So the question itself is clearly loaded, perhaps unintentionally (or perhaps not). Still, the question was asked, so here goes:

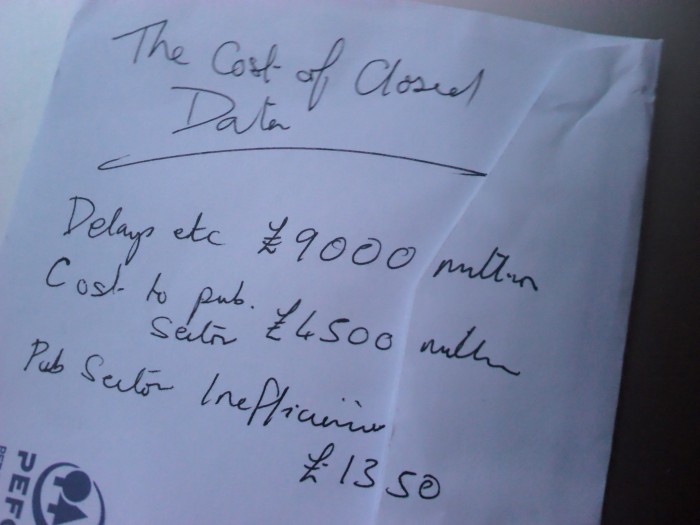

I’m going to address this in a somewhat reverse way (a sort of proof-by-contradiction). That is, rather than work out the difference between an open data world and a closed data one by estimating the increase from the current closed data world, I’m going to work out the costs to the UK incurred by having closed data.

Note that extensive use is made of Fermi estimates and backs of envelopes

- Increased costs to the UK of delays and frustrations. Twice this week I have waited around for more than 10 minutes for buses, time when I could have stayed in the coffee shop I was working in and carried on working on my laptop had I known when the next bus was coming.

Assuming I’m fairly unremarkable here and the situation happens to say 10 per cent of the UK’s working population through one form of transport or another, that means that there’s a loss of potential productivity of approx 0.04% (2390 minutes/2400 mins x 10%).

Similar factors apply to a whole number of other areas, closely tied to public sector data, from roadworks (not open data) to health information to education information (years after a test dump was published we still don’t have access to Edubase) – just examine a typical week and think of the number of times you were frustrated by something which linked to public information (strength of mobile signal?). So, assuming that the transport is a fairly significant 10% of the whole, and applying it to the UK $2.25 trillion GDP we get £9000 million. Not included: loss of activity due to stress, anger, knock-on effects (when I am late for a meeting I make attendees who are on time unproductive too), etc- Knock-on cost of data to public sector and associated administration. Taking the Ordnance Survey as an example of a Shareholder Executive body, of its £114m in revenue (and roughly equivalent costs), £74m comes from the public sector and utilities.

Although there would seem to be a zero cost in paying money from one organisation to another, this ignores the public sector staff and administration costs involved in buying, managing and keeping separate this info, which could easily be 30% of these costs, say 22 million. In addition, it has had to run a sales and marketing operation costing probably 14% of its turnover (based on staff numbers), and presumably it costs money collecting, formatting data which is only wanted by the private sector, say 10% of its costs.

This leads to extra costs of £22m + £16m + £14m = £52 million or 45%. Extrapolating that over the Shareholder Executive turnover of £20 billion, and discounting by 50% (on the basis that it may not be representative) leads to additional costs of £4500 million. Not included: additional costs of margin paid on public sector data bought back from the private (i.e. part of the costs when public sector buys public-sector-based data from the private sector is the margin/costs associated with buying the public sector data).- Significant decreases in exchange of information, and duplication of work within the public sector (not directly connected with purchase of public sector data). Let’s say that duplication, lack of communication, lack of data exchange increases the amount of work for the civil service by 0.5%. I have no idea of the total cost of the local & central govt civil service, but there’s apparently 450,000 of them, earning, costing say £60,000 each to employ, on the basis that a typical staff member costs twice their salary. That gives us an increased cost of £1350 million. Not included: cost of legal advice, solving licence chain problems, inability to perform its basic functions properly, etc.

- Increased fraud, corruption, poor regulation. This is a very difficult one to guess, as by definition much goes undetected. However, I’d say that many of the financial scandals of the past 10 years, from mis-selling to the FSA’s poor supervision of the finance industry had a fertile breeding ground in the closed data world in which we live (and just check out the FSA’s terms & conditions if you don’t believe me). Not to mention phoenix companies, one hand of government closing down companies that another is paying money to, and so on. You could probably justify any figure here, from £500 million to £50 billion. Why don’t we say a round billion. Not included: damage to society, trust, the civic realm

- Increased friction in the private sector world. Every time we need a list of addresses from a postcode, information about other companies, or any other public sector data that is routinely sold, we not only pay for it in the original cost, but for the markups on that original cost from all the actors in the chain. More than that, if the dataset is of a significant capital cost, it reduces the possible players in the market, and increases costs. This may or may not appear to increase GDP, but it does so in the same way that pollution does, and ultimately makes doing business in the UK more problematic and expensive. Difficult to put a cost on this, so I won’t.

- I’m also going to throw in a few billion to account for all the companies, applications and work that never get started because people are put off by the lack of information, high barriers to entry, or plain inaccessibility of the data (I’m here taking the lead from the planning reforms, which are partly justified on the basis that many planning applications are not made because of the hassle in doing them or because they would be refused, or otherwise blocked by the current system.)

What I haven’t included is reduced utilisation of resources (e.g empty buses, public sector buildings – the location of which can’t be released due to Ordnance Survey restrictions, etc), the poor incentives to invest in data skills in the public sector and in schools, the difficulty of SMEs understanding and breaking into new markets, and the inability of the Big Society to argue against entrenched interests on anything like and equal footing.

And this last point is crucial if localism is going to mean more rather than less power for the people.

So where does that leave us. A total of something like:

£17,850 million.

That, back of the envelope-wise, is what closed data is costing us, the loss through creating artificial scarcity by restricting public sector data to only those pay. Like narrowing an infinitely wide crossing to a small gate just so you can charge – hey, that’s an idea, why not put a toll booth on every bridge in London, that would raise some money – you can do it, but would that really be a good idea?

And for those who say the figures are bunk, that I’ve picked them out of the air, not understood the economics, or simply made mistakes in the maths – well, you’re probably right. If you want me to do better give me those Treasury economists, and the resources to use them, or accept that you’re only getting the voice of those that do, and not innovative SMEs, still less the Big Society.

Footnote: On a similar topic, but taking a slightly different tack is the ever excellent David Eaves on the economics of Toronto’s transport data. Well worth reading.

Update 15/10/2011: Removed line from 3rd para: ” (it’s also a concern that we’re actually the only company attending that’s consuming and publishing open data)” . In the event it turned out there were a couple other SMEs too working with open data day-to-day, but we were massively outnumbered by parts of government and companies whose existing models were to a large degree based on closed data. Despite this there wasn’t a single good word to be heard in favour of the Public Data Corporation, and many, many concerns that it was going down the wrong route entirely.

The Public Data Corporation vs Good Governance

As I feared back when it was first announced, the proposed UK Public Data Corporation has got nothing to do with open data, and everything to do with protecting the interests of a few civil servants, turning back the open data clock to the dark ages of derived data and privileged access for the few.

However, the issue I’d like to focus on here, having last week attended a workshop on the PDC consultation is governance. [It’s worth mentioning that I was the only one at the workshop without a stake in the existing public sector information structure, telling in itself.] And far from it being a dry, academic, wonkish subject, it is critical to the future of public data in the UK.

The reason this is so contentious is twofold:

- The consultation on the PDC has been drawn very narrowly, trying to get respondants to choose between a set of options that are all bad for open data, and ultimately democracy. “So, open data, would you like a bullet to the back of the head, or to be slowly drained of blood?”

- There are clear conflicts of interest between the wider interests of society, and those of the Shareholder Executive – the trading funds such as the Ordnance Survey and Land Registry who are the very roadblock that open data is supposed to clear, but yet who crucially seem to be driving the PDC.

Now, from their perspective, I can see the appeal of keeping everything cosy and tight, particularly if there’s a chance the organisations being floated off, and with it considerable personal enrichment. But public policy shouldn’t be driven by the personal interests of civil servants, but what is in the interests of society as a whole.

In fact, the governance of the Public Data Corporation, and the rules by which it operates were the one thing that everyone at the workshop I attended agreed upon. In fact more than that, it was agreed that the delivery of its duties should be separate both from the principles by which it operates (which should be for the benefit of society) and the independent body that needs to ensure it sticks to those principles.

But here’s the kicker, the Transition Board for the PDC (which will oversee its membership, structure and governance) is, I understand, meeting on October 25, two days before the consultation ends.

When I asked this meeting, and whether the consultation was a done deal, I was told, “The governance of the PDC is not being consulted on.”

This is both rather shocking, and shameful, and for me means there’s only one viable option if the UK is serious about open data: to send the whole PDC concept back to the drawing board, and this time to come up with a solution that is focused not on civil servants’ narrow personal interests, but on building a ‘more open, more fair and more prosperous‘ society (to quote the Chancellor).

When Washington DC took a step back from open data & transparency

When the amazing Emer Coleman first approached me a year and a half to get feedback on the plans for the London datastore, I told her that the gold standard for such datastores was that run by the District of Columbia, in the US. It wasn’t just the breadth of the data; it was that DC seemed to have integrated the principles of open data right into its very DNA.

And we had this commitment in mind that when we were thinking which were the US jurisdictions we’d scrape first for OpenCorporates, whose simple (but huge) goal is to build an open global database of every registered company in the world.

While there were no doubt many things that the DC company registry could be criticised for (perhaps it was difficult for the IT department to manage, or problematic for the company registry staff), for the visitors who wanted to get the information it worked pretty well.

What do I mean by worked well? Despite or perhaps because it was quite basic, it meant you could use any browser (or screenreader, for those with accessibility issues) to search for a company and to get the information about it.

It also had a simple, plain structure, with permanent URLs for each company, meaning search engines could easily find the data, so that if you search for a company name on Google there’s a pretty good chance you’ll get a link to the right page. This also means other websites can ‘deep-link’ to the specific company, and that links could be shared by people, in social networking, emails, whatever.

Finally, it meant that it was easy to get the information out of the register, by browsing or by scraping (we even used the scraper we wrote on ScraperWiki as an example of how to scrape a straightforward company register as part of our innovative bounty program).

It was, for the most part, what a public register should be, with the exception of providing a daily dump of the data under an open licence.

So it was a surprise a couple of weeks ago to find that they had redone the website, and taken a massive step back, essentially closing the site down to half the users of the web, and to those search engines and scrapers that wanted to get the information in order to make it more widely available.

In short it went from being pretty much open, to downright closed. How did they do this? First they introduced a registration system. Now, admittedly, it’s a pretty simple registration process, and doesn’t require you to submit any personal details. I registered as ‘Bob’ with a password of ‘password’ just fine. But as well as adding friction to the user experience, it also puts everything behind the signup out of the reach of search engines. Really dumb. Here’s the Google search you get now (a few weeks ago there were hundreds of thousands of results):

The other key point about adding a registration system is that the sole reason is to be able to restrict access to certain users. Let me repeat that, because it goes to the heart of the issue about openness and transparency, and why this is a step back from both by the District of Columbia: it allows them to say who can and can’t see the information.

If open data and transparency is about anything, it’s about giving equal access to information no matter who you are.

The second thing they did was build a site that doesn’t work for those who don’t use Internet Explorer 7 and above, including those who used screenreaders. That’s right. In the year 2011, when even Microsoft are embracing web standards, they decided to ditch them, and with them nearly half the web’s users, and all those who used screenreaders (Is this even allowed? Not covered by Americans With Disabilities Act?).

In the past couple of weeks, I’ve been in an email dialogue with the people in the District of Columbia behind the site, to try to get to the bottom of this, and the bottom seems to be, that the accessibility of the site, the ability for search engines to index it, and for people to reuse the data isn’t a priority.

In particular it isn’t a priority compared with satisfying the needs of their ‘customers’, meaning those companies that file their information (and perhaps more subtly those companies whose business models depend on the data being closed). Apparently some of the companies had complained that they were being listed, contacted and or solicited without their approval.

That’s right, the companies on the public register were complaining that their details were public. Presumably they’d really rather nobody had this information. We’re talking about companies here, remember, who are supposed to thrive or fail in the brutal world of the free market, not vulnerable individuals.

It’s worth mentioning here that this tendency to think that the stakeholders (hate that word) are those you deal with day-to-day is a pervasive problem in government in all countries, and is one of the reasons why they are failing to benefit from open data the way they should and failing too to retool and restructure for the modern world.

Sure, we can work around these restrictions and probably figure out a way to scrape the data, but it’s a sad day to see one of the pioneers of openness and transparency take such a regressive step. What’s next? Will the DC datastore take down its list of business licence holders, or maybe the DC purchase order data, all of which could be used for making unsoliticited requests to these oversensitive and easily upset businesses?

p.s. Apparently this change was in response to an audit report, which I’ve asked for a copy of but which hasn’t yet been sent to me. Any sleuthing or FOI requests gratefully received.

p.p.s. I also understand there’s also new DC legislation that’s been recently been passed that require further changes to the website, although again the details weren’t given to me, and I haven’t had time to search the DC website for them

George Osborne’s open data moment: it’s the Treasury, hell yeah

As a bit of an outsider, reading the government’s pronouncements on open data feels rather like reading official Kremlin statements during the Cold War. Sometimes it’s not what they’re saying, it’s who’s saying it that’s important.

And so it is, I think, with George Osborne’s speech yesterday morning at Google Zeitgeist, at which he stated, “Our ambition is to become the world leader in open data, and accelerate the accountability revolution that the internet age has unleashed“, and “The benefits are immense. Not just in terms of spotting waste and driving down costs, although that consequence of spending transparency is already being felt across the public sector. No, if anything, the social and economic benefits of open data are even greater.”

This is strong, and good stuff, and that it comes from Osborne, who’s not previously taken a high profile position on open data and open government, leaving that variously to the Cabinet Office Minister, Francis Maude, Nick Clegg & even David Cameron himself.

It’s also intriguing that it comes in the apparent burying of the Public Data Corporation, which got just a holding statement in the budget, and no mention at all in Osborne’s speech.

But more than that it shows the Treasury taking a serious interest for the first time, and that’s both to be welcomed, and feared. Welcomed, because with open data you’re talking about sacrificing the narrow interests of small short-term fiefdoms (e.g. some of the Trading Funds in the Shareholder Executive) for the wider interest; you’re also talking about building the essential foundations for the 21st century. And both of these require muscle and money.

It also overseas a number of datasets which have hitherto been very much closed data, particularly the financial data overseen by the Financial Services Authority, the Bank of England and even perhaps some HMRC data, and I’ve started the ball rolling by scraping the FSA’s Register of Mutuals, which we’ve just imported into OpenCorporates, and tying these to the associated entries in the UK Register of Companies.

Feared, because the Treasury is not known for taking prisoners, still less working with the community. And the fear is that rather than leverage the potential that open data allows for a multitude of small distributed projects (many of which will necessarily and desirably fail), rather than use the wealth of expertise the UK has built up in open data, they will go for big, highly centralised projects.

I have no doubt, the good intentions are there, but let’s hope they don’t do a Team America here (and this isn’t meant as a back-handed reference to Beth Noveck, who I have a huge amount of respect for, and who’s been recruited by Osborne), and destroy the very thing they’re trying to save.

Videoing council meetings redux: progress on two fronts

Tonight, hyperlocal bloggers (and in fact any ordinary members of the public) got two great boosts in their access to council meetings, and their ability to report on them.

Windsor & Maidenhead this evening passed a motion to allow members of the public to video the council meetings. This follows on from my abortive attempt late last year to video one of W&M’s council meeting – see the full story here, video embedded below – following on from the simple suggestion I’d made a couple of months ago to let citizens video council meetings. I should stress that that attempt had been pre-arranged with a cabinet member, in part to see how it would be received – not well as it turned out. But having pushed those boundaries, and with I dare say a bit of lobbying from the transparency minded members, Windsor & Maidenhead have made the decision to fully open up their council meetings.

Separately, though perhaps not entirely coincidentally, the Department for Communities & Local Government tonight issued a press release which called on councils across the country to fully open up their meetings to the public in general and hyperlocal bloggers in particular.

Councils should open up their public meetings to local news ‘bloggers’ and routinely allow online filming of public discussions as part of increasing their transparency, Local Government Secretary Eric Pickles said today.

To ensure all parts of the modern-day media are able to scrutinise Local Government, Mr Pickles believes councils should also open up public meetings to the ‘citizen journalist’ as well as the mainstream media, especially as important budget decisions are being made.

Local Government Minister Bob Neill has written to all councils urging greater openness and calling on them to adopt a modern day approach so that credible community or ‘hyper-local’ bloggers and online broadcasters get the same routine access to council meetings as the traditional accredited media have.

The letter sent today reminds councils that local authority meetings are already open to the general public, which raises concerns about why in some cases bloggers and press have been barred.

Importantly, the letter also tells councils that giving greater access will not contradict data protection law requirements, which was the reason I was given for W&M prohibiting me filming.

So, hyperlocal bloggers, tweet, photograph and video away. Do it quietly, do it well, and raise merry hell in your blogs and local press if you’re prohibited, and maybe we can start another scoreboard to measure the progress. To those councils who videocast, make sure that the videos are downloadable under the Open Government Licence, and we’ll avoid the ridiculousness of councillors being disciplined for increasing access to the democratic process.

And finally if we can collectively think of a way of tagging the videos on Youtube or Vimeo with the council and meeting details, we could even automatically show them on the relevant meeting page on OpenlyLocal.

What’s that coming over the hill, is it… the Public Data Corporation?

A couple of days ago, there was a brief announcement from the UK Government of plans for a new Public Data Corporation, which would “bring together Government bodies and data into one organisation”.

A good thing, no? Well, up to a point, Lord Copper.

I tweeted after the announcement: “Is it just me, or does the tone of the Public Data Corp make any other #opendata types uneasy?” From the responses, I clearly wasn’t the only one, and in my discussions since then it’s clear there’s a lot of nervousness out there.

So, what is it, and should we be afraid? The answers are ‘Nobody knows’, and ‘Yes’.

To flesh that out a bit, none of the open data activists and developers that I’ve spoken to knows what it is, or what the real motivation is, and remember these are the people who did much to get us into a place where the UK government has declared that the public has a ‘Right To Data’ and that the excellent ‘Open Government Licence‘ should be the default licence.

In that context, the announcement of a ‘Public Data Corporation’ should be be treated with some wariness.

However, this wariness turns into suspicion, when you read the press release.

First the announcement is a joint one from the Cabinet Office minister Francis Maude (who seems to very much get the need for open public data in the changed world in which we live) and from Business Minister Edward Davey, who I know nothing about, but his department BIS (Dept of Business, Innovation & Skills) has very much not been pushing for open data, and in fact has in the past refused to make data it oversees openly available.

(My sources tell me the proposal in fact originated from BIS, and thus could be seen as an attempt by the incumbents to co-opt the open data agenda, as a way of shutting it down, smothering it if you like.)

Second, despite the upbeat headline “Public Data Corporation to free up public data and drive innovation” (Shock horror: org states its aim is to innovate & be successful), the text contains a number of worrying statements:

- “By bringing valuable Government data together, governed by a consistent set of principles around data collection, maintenance, production and charging[my emphasis], the Government can share best practice, drive efficiencies and create innovative public services for citizens and businesses. The Public Data Corporation will also provide real value for the taxpayer.”

The idea of ‘value for the taxpayer’ is the same old stuff that got us into the unholy mess of trading funds, and the gordian knot of the Ordnance Survey licence wich is still being unpicked. This nearly always translates as value we can measure in £s, which in turn means what income we’ve got coming in (even if it’s from other public sector bodies). - “It will provide stability and certainty for businesses and entrepreneurs, attracting the investment these operations need to maintain their capabilities and drive growth in the economy” – quote from Edward Davey.

If I were a cynic I’d say stability and certainty translates to stagnation and rent-seeking businesses, which may be music to civil servants’ ears but does nothing to help innovation. We’re in a rapidly changing world. Get over it. - “bringing valuable Government data together, governed by a consistent set of principles around data collection, maintenance, production and charging”.

If this is the PDC’s mandate I think it could end up focused on the last of these, short-sighted though that would be. - “It will also provide opportunities for private investment in the corporation.”

Great. A conflicting priority, to delight the bureaucrats and muddy the focus. Keep it small, keep it simple, keep it agile.

Finally, there’s no mention of open data, no mention of the Open Government Licence, the Transparency Board and only one mention of transparency, and that’s in Francis Maude’s quote.

As Tom Steinberg (a member of the Transparency Board) wrote in a thread about the PDC on MySociety developer mailing list ”

If you’re a natural cynic, you’ll just say the government has already decided to flog everything off to the highest bidder. If you adopt that position, and give up without a fight, the people in Whitehall and the trading funds who want to do that will almost certainly win.

However, if you believe me when I say things are finely balanced, that either side could win, and enough well-organised external pressure could really make a difference over the next year, then you won’t just bitch, you’ll get stuck in.

He’s not wrong there. We’ve got perhaps 6 months to make this story turn out good for open data, and good for the wider community, and I suspect that means some messy battles along the way, forcing government to take the right path rather than slide into its bad old habits, perhaps with some key datasets, which should undoubtedly be public open data, but are currently under a restrictive licence.

I’ve got a couple in my sights. Watch this space.

Not the way to build a Big Society: part1 NESTA

I took a very frustrating phone call earlier today from NESTA, an organisation I’ve not had any dealings with it before, and don’t actually have a view about it, or at least didn’t.

It followed from an email I’d received a couple of days earlier, which read:

I am contacting you about a project NESTA are currently working on in partnership with the Big Society Network called Your Local Budget.

Working with 10 pioneer local authorities, we are looking at how you can use participatory budgeting to develop new ways to give people a say in how mainstream local budgets are spent. Alongside this we will also be developing an online platform that enables members of the public to understand and scrutinise their local authority’s spending, and connect with each other to generate ideas for delivering better value for money in public spending.

We would like to share our thinking and get your thoughts on the online tool to get a sense of what is needed and where we can add value. You are invited to a round table discussion on Friday 19 November, 11am – 12.30pm at NESTA that will be chaired by Philip Colligan, Executive Director of the Public Services Lab. Following the meeting we intend to issue an invitation to tender for the online tool.

Apart from the short notice & terrible timing (it clashes with the Open Government Data Camp, to which you’d hope most of the people involved would be going), the main question I had was this:

Why?

I got the phone call because I couldn’t make the round table, and for some feedback, and this was the feedback I gave: I don’t understand why this is being done. At all.

Putting aside the participatory budgeting part (although this problem seems to be getting dealt with by Redbridge council and YouGov, whose solution is apparently being offered to all councils), there’s the question of the “online platform that enables members of the public to understand and scrutinise their local authority’s spending, and connect with each other to generate ideas for delivering better value for money in public spending.”

Excuse me? Most of the data hasn’t been published yet, there are several known organisations and groups (including OpenlyLocal) that have publicly stated they going to to be importing this data and doing things with it – visualising it, and allowing different views and analysis. Additionally, OpenlyLocal is already talking with several newspaper groups to help them re-use the data, and we are constantly evolving how we match and present the data.

Despite this, Nesta seems to have decided that it’s going to spend public money on coming up with a tendered solution to solve a problem that may be solved for zero cost by the private sector. Now I’m no roll-back-the-government red-in-tooth-and-claw free marketeer, but this is crazy, and I said as much to the person from Nesta.

Is the roundtable to decide whether the project should be done, or what should be done? I asked. The latter I was told. So, they’ve got some money and have decided they’re going to spend it, even though the need may not be there. At a time when welfare payments are being cut, essential services are being slashed, for this sort of thing to happen is frankly outrageous.

There are other concerns here too – I personally think websites such as this are not suitable for a tender process, as that doesn’t encourage or often even allow the sort of agile, feedback-led process that produces the best websites. They also favour those who make their living by tendering.

So, Nesta, here’s a suggestion. Park this idea for 12 months, and in the meantime give the money back to the government. If you want to act as an angel funding then act as such (and the ones I’ve come across don’t do tendering). A reminder, your slogan is ‘making innovation flourish’, but sometimes that means stepping back and seeing what happens. This is not the way to building a Big Society

Open data, fraud… and some worrying advice

One of the most commonly quoted concerns about publishing public data on the web is the potential for fraud – and certainly the internet has opened up all sorts of new routes to fraud, from Nigerian email scams, to phishing for bank accounts logins, to key-loggers to indentity theft.

Many of these work using two factors – the acceptance of things at face value (if it looks like an email from your bank, it is an email from them), and flawed processes designed to stop fraud but which inconvenience real users while making life easy from criminals.

I mention this because of some pending advice from the Local Government Association to councils regarding the publication of spending data, which strikes me as not just flawed, but highly dangerous and an invitation to fraudsters.

The issue surrounds something that may seem almost trivial, but bear with me – it’s important, and it’s off such trivialities that fraudsters profit.

In the original guidance for councils on publishing spending data we said that councils should publish both their internal supplier IDs and the supplier VAT numbers, as it would greatly aid the matching of supplier names to real-world companies, charities and other organisations, which is crucial in understanding where a local council’s money goes.

When the Local Government Association published its Guidance For Practitioners it removed those recommendations in order to prevent fraud. It has also suggested using the internal supplier ID as a unique key to confirm supplier identity. This betrays a startling lack of understanding, and worse opens up a serious vector to allow criminals to defraud councils of large sums of money.

Let’s take the VAT numbers first. The main issue here appears to be so-called missing trader fraud, whereby VAT is fraudulently claimed back from governments. Now it’s not clear to me that by publishing VAT numbers for supplier names that this fraud is made easier, and you would think the Treasury who recommend publishing the VAT numbers for suppliers in their guidance (PDF) would be alert to this (I’m told they did check with HMRC before issuing their guidance).

However, that’s not the point. If it’s about matching VAT numbers to supplier names there’s already several routes for doing this, with the ability to retrieve tens of thousands of them in the space of an hour or so, including this one:

http://www.google.co.uk/#sclient=psy&hl=en&q=%27vat+number+gb%27+site:com

Click on that link and you’ll get something like this:

Whether you’re a programmer or not, you should be able to see that it’s a trivial matter to go through those thousands of results and extract the company name and VAT number, and bingo, you’ve got that which the LGA is so keen for you not to have. So those who are wanting to match council suppliers don’t get the help a VAT number would give, and fraudsters aren’t disadvantaged at all.

Now, let’s turn to the rather more serious issue of internal Supplier IDs. Let me make it clear here, when matching council or central government suppliers, internal Supplier IDs are useful, make the job easier, and the matching more accurate, and also help with understanding how much in total redacted payees are receiving (you’d be concerned if a redacted person/company received £100,000 over the course of a year, and without some form of supplier ID you won’t know that). However, it’s not some life-or-death battle over principle for me.

The reason the LGA, however, is advising councils not to publish them is much more serious, and dangerous. In short, they are proposing to use the internal Supplier ID as a key to confirm the suppliers identity, and so allow the supplier to change details, including the supplier bank account (the case brought up here to justify this was the recent one of South Lanarkshire, which didn’t involve any information published as open data, just plain old fraudster ingenuity).

Just think about that for a moment, and then imagine that it’s the internal ID number they use for you in connection with paying your housing benefits. If you want to change your details, say you wanted to pay the money into a different bank account, you’d have to quote it – and just how many of us would have somewhere both safe to keep it and easy to find (and what about when you separated from your partner).

Similarly, where and how do we really think suppliers are going to keep this ID (stuck on a post-it note to the accounts receivable’s computer screen?), and what happens when they lose it? How do they identify themselves to find out what it is, and how will a council go about issuing a new one should the old one be compromised – is there any way of doing this except by setting up a new supplier record, with all the problems that brings.

And how easy would it be to do a day or two’s temping in a council’s accounts department and do a dump/printout of all the Supplier IDs, and then pass them onto fraudsters. The possibilities – for criminals – are almost limitless, and the Information Commissioner’s Office should put a stop to this at once if it is not to lose a serious amount of credibility.

But there’s an bigger underlying issue here, and it’s not that organisations such as the LGA don’t get data (although that is a problem), it’s that such bodies think that by introducing processes they can engineer out all risk, and that leads to bad decisions. Tell someone that suppliers changing bank accounts is very rare and should always be treated with suspicion and fraud becomes more difficult; tell someone that they should accept internal supplier IDs as proof of identity and it becomes easy.

Government/big-company bureaucrats not only think like government/big-company bureaucrats, they build processes that assumes everyone else does. The problem is that that both makes more difficult for ordinary citizens (as most encounters with bureaucracy make clear), and also makes it easy for criminals (who by definition don’t follow the rules).

Opening up council accounts… and open procurement

Since OpenlyLocal started pulling in council spending data, it’s niggled at me that it’s only half the story. Yes, as more and more data is published you’re beginning to get a much clearer idea of who’s paid what. And if councils publish it at a sufficient level of detail and consistently categorised, we’ll have a pretty good idea of what it’s spent on too.

However, useful though that is, that’s like taking a peak at a company’s bank statement and thinking it tells the whole story. Many of the payments relate to goods or services delivered some time in the past, some for things that have not yet been delivered, and there are all sorts of things (depreciation, movements between accounts, accruals for invoices not yet received) that won’t appear on there.

That’s what the council’s accounts are for — you know, those impenetrable things locked up in PDFs in some dusty corner of the council’s website, all sufficiently different from each other to make comparison difficult:

For some time, the holy grail for projects like OpenlyLocal and Where Does My Money Go has been to get the accounts in a standardized form to make comparison easy not just for accountants but for regular people too.

The thing is, such a thing does exist, and it’s sent by councils to central Government (the Department for Communities and Local Government to be precise) for them to use in their own figures. It’s a fairly hellishly complex spreadsheet called the Revenue Outturn form that must be filled in by the council (to get an idea have a look at the template here).

They’re not published anywhere by the DCLG, but they contain no state secrets or sensitive information; it’s just that the procedure being followed is the same one as they’ve always followed, and so they are not published, even after the statistics have been calculated from the data (the Statistics Act apparently prohibit publication until the stats have been published).

So I had an idea: wouldn’t it be great if we could pull the data that’s sitting in all these spreadsheets into a database and so allow comparison between councils’ accounts, thus freeing it from those forgotten corners of government computers.

This would seem to be a project that would be just about simple enough to be doable (though it’s trickier than it seems) and could allow ordinary people to understand their council’s spending in all sorts of ways (particularly if we add some of those sexy Where Does My Money Go visualisations). It could also be useful in ways that we can barely imagine – some of the participatory budget experiments going in on in Redbridge and other councils would be even more useful if the context of similar councils spending was added to the mix.

So how would this be funded. Well, the usual route would be for DCLG or perhaps the one of the Local Government Association bodies such as IDeA to scope out a proposal, involving many hours of meetings, reams of paper, and running up thousands of pounds in costs, even before it’s started.

They’d then put the process out to tender, involving many more thousands in admin, and designed to attract those companies who specialise in tendering for public sector work. Each of those would want to ensure they make a profit, and so would work out how they’re going to do it before quoting, running up their own costs, and inflating the final price.

So here’s part two of my plan, instead going down that route, I’d come up with a proposal that would:

- be a fraction of that cost

- be specified on a single sheet of paper

- paid for only if I delivered

Obviously there’s a clear potential conflict of interest here – I sit on the government’s Local Public Data Panel and am pushing strongly for open data, and also stand to benefit (depending on how good I am at getting the information out of those hundreds of spreadsheets, each with multiple worksheets, and matching the classification systems). The solution to that – I think – is to do the whole thing transparently, hence this blog post.

In a sense, what I’m proposing is that I scope out the project, solving those difficult problems of how to do it, with the bonus of instead of delivering a report, I deliver the project.

Is it a good thing to have all this data imported into a database, and shown not just on a website in a way non-accountants can understand, but also available to be combined with other data in mashups and visualisations? Definitely.

Is it a good deal for the taxpayer, and is this open procurement a useful way of doing things? Well you can read the proposal for yourself here, and I’d be really interested in comments both on the proposal and the novel procurement model.

New feature: one-click FoI requests for spending payments

Thanks to the incredible work of Francis Irving at WhatDoTheyKnow, we’ve now added a feature I’ve wanted on OpenlyLocal since we started imported the local spending data: one-click Freedom of Information requests on individual spending items, especially those large ones.

This further lowers the barriers to armchair auditors wanting to understand where the money goes, and the request even includes all the usual ‘boilerplate’ to help avoid specious refusals. I’ve started it off with one to Wandsworth, whose poor quality of spending data I discussed last week.

And this is the result, the whole process having taken less than a minute:

The requests are also being tagged. This means that in the near future you’ll be able to see on a transaction page if any requests have already been made about it, and the status of those requests (we’re just waiting for WDTK to implement search by tags), which will be the beginning of a highly interconnected transparency ecosystem.

In the meantime it’s worth checking the transaction hasn’t been requested before confirming your request on the WDTK page (there’s a link to recent requests for the council on the WDTK form you get to after pressing the button).

I’m also trusting the community will use this responsibly, digging out information on the big stuff, rather than firing off multiple requests to the same council for hundreds of individual items (which would in any case probably be deemed vexatious under the terms of the FoI Act). At the moment the feature’s only enabled on transactions over £10,000.

Good places to start would be those multi-million-pound monthly payments which indicate big outsourcing deals, or large redacted payments (Birmingham’s got a few). Have a look at the spending dashboard for your council and see if there are any such payments.